Is That Black Enough for You?!?

The critic-turned-filmmaker Elvis Mitchell provides an absorbing view of a key decade in black cinema.

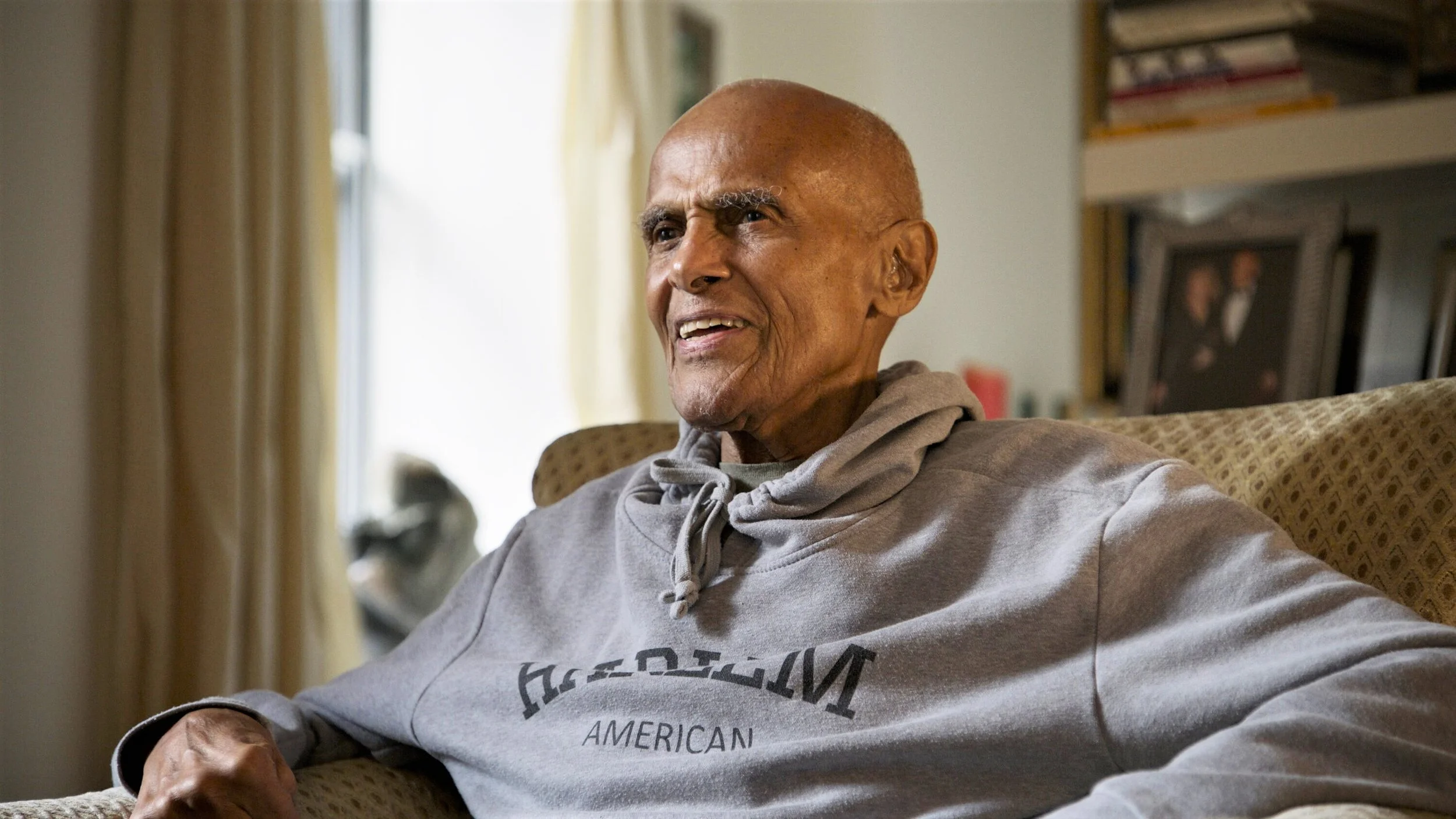

Harry Belafonte

I have always held the view that the work of a film critic involves reporting on the interaction between whatever film he or she is watching and their own sensibility. That's a notion that helps to explain why this documentary feature about black cinema could only have been made with such distinction by someone like Elvis Mitchell. Mitchell is a well-established American film critic who in Is That Black Enough for You?!? has given us his first feature film and he not only directed it but provided its narrative which he speaks himself. Since the title is a quote from the 1971 classic Cotton Comes to Harlem, it was no surprise to learn that Mitchell had chosen to focus for the most part on films made between 1968 and 1978 albeit that movies from earlier decades would not be ignored altogether. In anticipation this documentary promised to be a useful look at a key decade in black cinema, one during which the term ‘Blaxploitation’ became familiar. But in the event what Mitchell has given us turns out to offer much more than that would suggest for this is a film with a highly original approach.

With Mitchell being a critic-turned-filmmaker, one might have expected that his film would contain critiques of the movies featured in it but that proves rarely to be the case. He rejects too the notion of analysing any film’s technique, eschewing the style of that other critic-turned-filmmaker Mark Cousins. Instead, he utilises his passion for cinema and his knowledge as a film historian to examine what the changing screen presentations of black characters have meant to viewers like himself who, being black, looked to the cinema in the hope of seeing their own lives reflected there. Thus, Is That Black Enough for You?!? is deeply expressive of his own sensibility and that of black audiences generally regarding what they were - or were not - offered in that respect.

If that is the spirit in which Mitchell's own insightful narration is offered, it also extends to the film’s interview footage with the likes of Charles Burnett, Laurence Fishburne, Mario Van Peebles, Whoopi Goldberg, Billy Dee Williams and Samuel L. Jackson. Most striking of all the interviews is that with Harry Belafonte whose artistic integrity and honest comments impress greatly. At 135 minutes the film is lengthy and it might just possibly be better still if it had been slightly pruned, but that hardly matters when there is so much on offer that impresses. Be it Mitchell’s reminiscences about his grandmother (she adored old films and shared her enthusiasm with him despite their limited and unsympathetic treatment of black characters) or clips from numerous films both established and largely forgotten, there is real value here. How intriguing, for example, to learn of Jules Dassin’s Uptight (1968) with its black cast and to discover that the Czech filmmaker Ján Kádar, noted for 1965’s The Shop on the Main Street, went to America and made The Angel Levine in 1970 starring Ida Kaminska from the 1965 film alongside Harry Belafonte and Zero Mostel. It's fascinating too to hear Glynn Turman revealing how Ingmar Bergman sought him out in the 1970s for a role in The Serpent’s Egg after seeing him in Cooley High and to be told of Steve McQueen’s support for Rupert Crosse despite the latter having been outspoken and not deferential when visiting the star to discuss the possibility of being cast in The Reivers (1969).

Aside from these incidentals, Mitchell's film paints a clear picture of changing times for black actors and for the roles available to them: the growth to larger parts in independent pictures, mainstream approval growing through the success of Sidney Poitier even if black actors would then work largely for white directors, the glamorisation that came once a black romantic lead was acceptable, the commercial success of black action movies with black stars as heroes or antiheroes and the opportunities at last for black filmmakers to direct mainstream movies. But, if this all sounded like a positive progression, it would become clear that Hollywood was embracing diversity only while the cash was flowing. As Mitchell points out, it was the end of an era and the end of the Blaxploitation trend when the 1978 movie The Wiz cost a fortune and then bombed at the box-office. A change of style and a new kind of action hero would take over, albeit that black cinema would in time return refreshed - but that is another story outside the scope of this film.

Another unexpected aspect that appeals here is Mitchell's knowledgeable awareness of the extent to which music contributed to the hits of the 1970s with such artists as Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield making a major contribution. The film is centred on America, which is fair enough, and it all comes across as deeply informative and possessed of a character all its own. But Mitchell’s triumph here is a shared one since no scenes outstay their welcome and the editing by Doyle Esch and Michael Engelken makes its own valuable contribution in this respect.

MANSEL STIMPSON

Featuring Harry Belafonte, Glynn Turman, Charles Burnett, Whoopi Goldberg, Laurence Fishburne, Samuel L. Jackson, Billy Dee Williams, Mario Van Peebles, Margaret Avery, Suzanne De Passe, Zendaya.

Dir Elvis Mitchell, Pro Ciara Lacy, Steven Soderbergh, David Fincher and Angus Wall, Screenplay Elvis Mitchell, Ph Justin Ervin, Ed Doyle Esch and Michael Engelken.

Makemake/Netflix-Netflix.

135 mins. USA. 2022. UK and US Rel: 11 November 2022. Cert. 15.