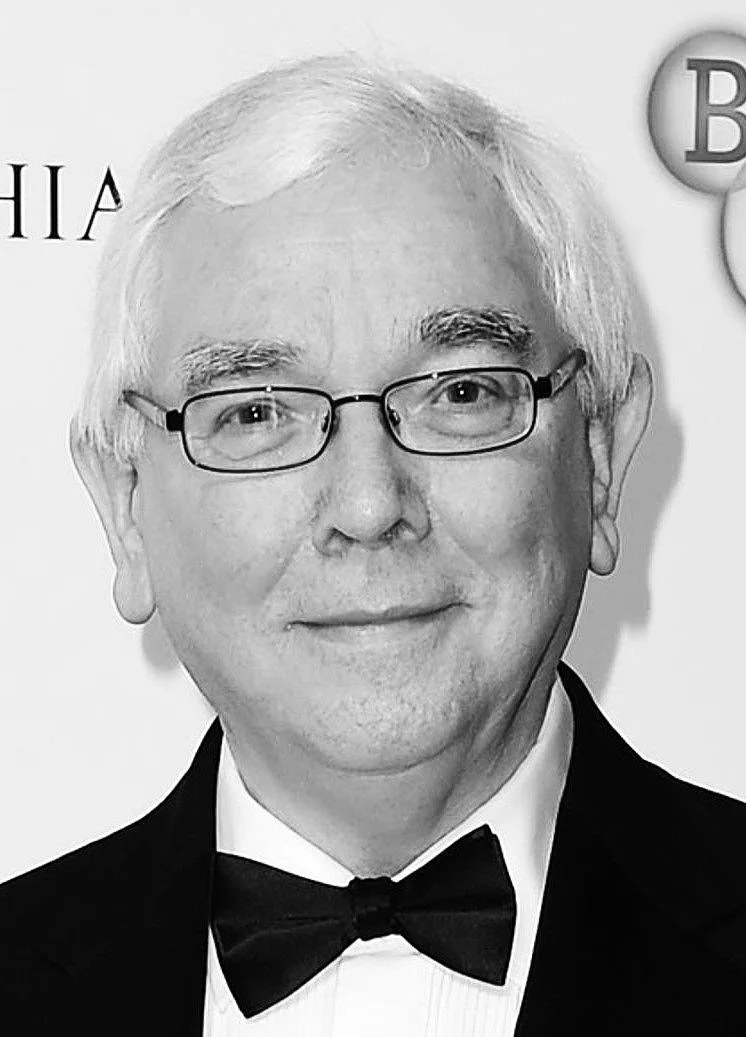

TERENCE DAVIES

(10 November 1945 - 7 October 2023)

The British screenwriter and director Terence Davies, who has died following a short illness at the age of 77, was one of Britain’s most important filmmakers, a true artist of the cinema. He was never a director who sought to make films just for profit. He prepared every project with the utmost care, so that over more than forty years he made only nine features and five shorts. He was born in Liverpool, the youngest of ten children and, although his parents were Catholic, their son later denounced their faith and turned atheist. His father, a brutal man who beat his family, died when Terence was seven and from then on the boy led a more carefree life. He left boarding school at 16 and worked as a shipping office clerk before training at the Coventry Drama School.

Whilst there he wrote the first of his short films, Childhood, which was made under the auspices of the British Film Institute. This got him a place at the National Film School where he made Madonna and Child and Death and Transfiguration. All three films were about his own life from birth to death and in 1983 they made a collection called The Terence Davies Trilogy. This did well, winning the Ecumenical Prize at the Locarno Festival, the first of many accolades that Davies’s work received in his career. Virtually all his films either won or were nominated for awards.

Davies will always have a place in the world of artistic endeavour. This is true for his first feature, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), his most nostalgic work about his early life in Liverpool, sourcing the music of the time along with the films, the pubs and other entertainments. The first part is about his own family and his abusive father. The second covers the family later on in better times with a real feeling of hope. The Long Day Closes was an account of his family and the start of his growing love for film as a form of escapism. It won the Evening Standard award for best screenplay.

After that Davies moved on to books he admired, the first being The Neon Bible (1995) by John Kennedy O’Toole, about David, a boy living in Georgia in the 1940s. Again, there is an abusive father who goes to war while David has to look after his mother. It was beautifully shot but not well received. However, it was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes, and Davies’s cinematographer, Michael Coulter, won an award at the Valladolid Festival. The House of Mirth was an adaptation of the 1905 novel by Edith Wharton about money and social attitudes, a delightful period piece evoking an era when position mattered more than anything. It starred Gillian Anderson who won best actress in the British Independent Film Awards.

The Deep Blue Sea was adapted from Terence Rattigan’s play about the wife of a High Court judge who has an affair with ex-RAF pilot but cannot face living in poverty – again a theme about social status and money. With great performances by Rachel Weisz, Simon Russell Beale and Tom Hiddleston, the New York Film Critics voted Weisz as best actress. Sunset Song was from the novel by Lewis Grassic Gibbon about a farm girl with an abusive father but an adoring family who eventually finds true happiness. Emily Dickinson, the subject of A Quiet Passion, was a reclusive American poet who never found love with a man she could marry. The director tells it with a personal slant in that Davies admitted to me in an interview that he had never had any lasting form of personal relationship, either with a woman nor, as he was gay, with any man. Benediction, Davies’s last feature in 2021, was a study of the British poet Siegfried Sassoon, a World War I hero, who wrote anti-war poetry and had gay affairs but eventually married, had a son and converted to Catholicism. This was an obvious choice for Davies who had rejected his own family’s Catholic beliefs. Jack Lowden as the young poet won a best actor award from Bafta Scotland and the film won awards at San Sebastian, Dublin and the Online Film Critics Society.

Davies also made a documentary about his early life in Liverpool, for which he used archive material and newsreel, a summary of his memories called Of Time and the City (2008). He narrated, quoting from famous poets and writers, with both classical and popular music of the 1950s and ‘60s, with shots of celebrities of the day and clips from Davies’s favourite films, all set against Liverpool landmarks in a tribute to his home city, a marvellous evocation of a life across many cultures. All his films will remain in the minds of filmgoers who wish to appreciate what a caring director can accomplish through the true art of the cinema.

MICHAEL DARVELL