Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Martin Scorsese is the perfect guide to the work of one of British cinema’s greatest partnerships.

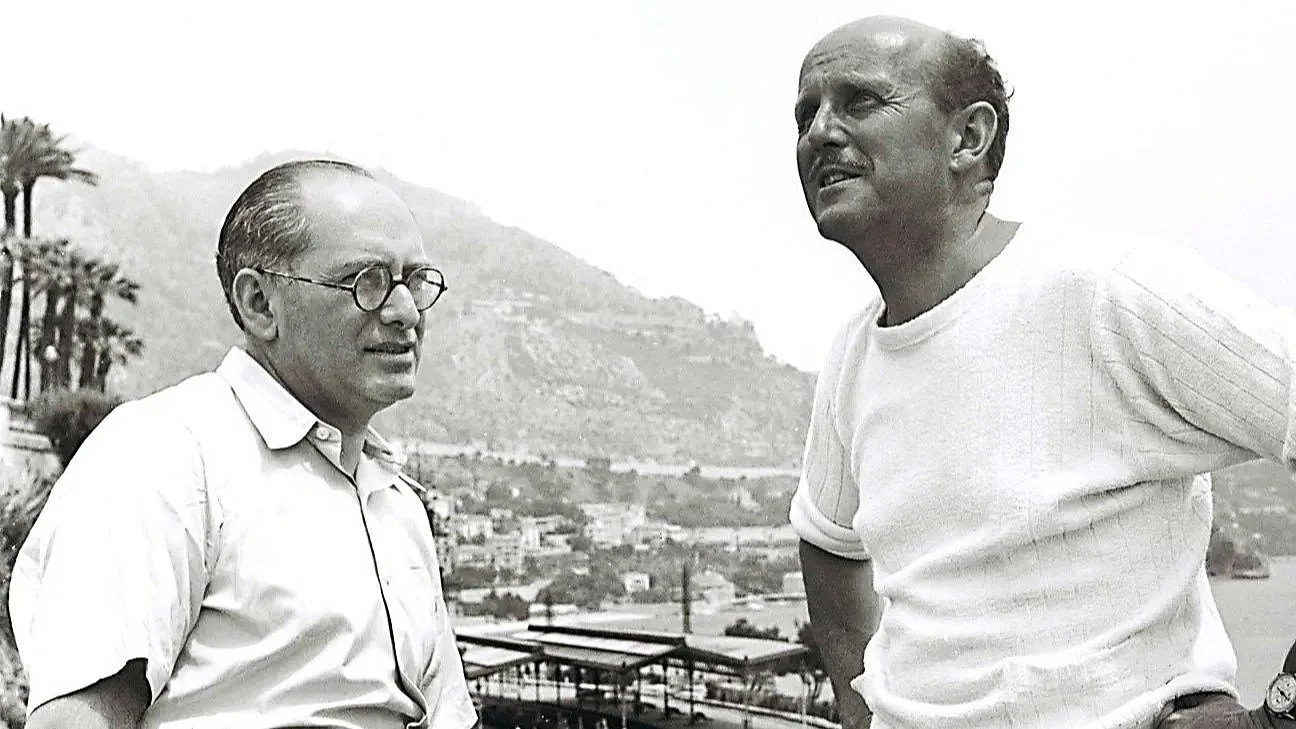

Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell

This is a very simple, straightforward piece of filmmaking but because the ingredients are so right it is also masterly. When aiming to make a documentary studying the work of that great filmmaking couple Powell and Pressburger nothing could be more fitting than to do it through the eyes of Martin Scorsese. The very presence here of the famed American director will help to sell this film to a younger audience for whom its subject matter is fresh territory while those who are already admirers will relish the opportunity to hear and see Scorsese analysing the work of this notable duo, Britain's Michael Powell and Hungary’s Emeric Pressburger, who teamed up to make films in England and did so for some sixteen years or more.

Anyone who has seen that epic documentary of 1995 entitled A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies or its equally lengthy successor on Italian Cinema, 1999’s My Voyage to Italy, will be aware of the insight and skill that Scorsese displays when talking about the films of others. Given his known admiration for Powell and Pressburger and his support for restorations of their films, it is no surprise that he is an ideal guide to what they achieved. His understanding of their work is further enhanced by two factors: his acknowledgement of how his own films have been influenced by theirs and the fact that in Powell’s later years he and Scorsese were friends as well as being close associates (in 1984 Powell married Scorsese’s celebrated editor Thelma Schoonmaker).

Although the director of this film, David Hinton, is best known for his television work, he is an apt choice since he won a Bafta award for his 1986 South Bank Show about Michael Powell. If this documentary, admirable as it is, cannot be described as the definitive film about this famous duo that is only because the richness of the material is such that no single film could achieve that. For one thing, the title of Hinton's film makes it clear that it will deal with the films rather than with the lives of Powell and Pressburger (early on we do get a brief sketch of their backgrounds and of their involvement in film ahead of their meeting as director and writer respectively on Alexander Korda’s 1939 movie The Spy in Black but what is covered is understandably limited). In addition, the emphasis that Scorsese puts on colour, light and movement in the films that they made together underlines the dominance of his concern with the visuals. He may refer to the importance of music in their work but you get no mention of Allan Gray or Brian Easdale nor is there any detailed mention of the production designer Hein Heckroth. Similarly, a whole study could be made of Powell and Pressburger’s relationships with their players, not least with their favourite actresses.

But if this defines the limits of Made in England it in no way undermines its quality. There is judicious use of interview footage of both Powell and Pressburger and of on-set moments too. We can recognise the obvious rapport (they remained friends even after they had ceased working together) and learn something of their individual contributions. It was Pressburger who was central to both story and structure but, after shared discussion, it would be Powell who played the key role in the shooting of each piece. It may well have been Powell’s love of Kent (where he was born) and of Scotland's Western Isles that led to A Canterbury Tale (1944) and I Know Where I'm Going! (1945) respectively, but it was Pressburger who argued for the young actress, Deborah Kerr, to play three roles in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and the fact that he had many German friends may have led to the sharp distinction drawn between Nazis and Germans of a sympathetic kind as featured not only in Blimp but in 49th Parallel (1941).

Welcome as this background information is, what counts most here is the perceptive non-technical way in which Scorsese can bring out his admiration for the films both as examples of artists remaining true to themselves even while working in mainstream cinema – their originality and often subversive ideas retained – and as instances of outstanding filmmaking (a number of short extracts from Scorsese’s films are included to illustrate his personal indebtedness). Quite rightly Scorsese is ready to acknowledge the duo’s failures such as The Elusive Pimpernel (1949), Oh, Rosalinda!! (1955) and Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) while the box-office hit from this late period, 1956’s The Battle of the River Plate, is described as no more than a conventional movie.

The only time that Scorsese’s viewpoint took me aback concerned The Small Back Room (1949) which he rightly praises but which he describes as being in the realist tradition without referring to one sequence in it which is the very reverse of that. He sees it too as a love story without giving any hint that its drama also features the diffusing of booby trap bombs in war-time and has all the tension of, say, The Hurt Locker (2008). That he should speak highly of Powell’s one late outstanding solo work (Peeping Tom of 1960) is both apt and unsurprising given its standing today (the hostile press it received initially is quoted here). He is awed too by The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) seeing it as a transcendent work offering opera as cinema by way of dance, but my own particular pleasure was to find him describing the still underrated Gone to Earth (1950) as a masterpiece.

Having known Powell personally, Scorsese sees him as a spirit who was strong and who never compromised in what he did. If he features more than Pressburger in this survey of their work, we are nevertheless left with an awareness of how vital it was for them to make films to which each contributed and to do so in such a way that these works were famously credited as “Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger". These may now be old films but their quality, further illuminated as it is by Scorsese’s comments, shines through in this documentary. It will surely leave all viewers anxious to see them whether to renew old acquaintance or to discover them in full for the first time. Your top choice might even be a title not mentioned above: A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Back Narcissus (1946) or The Red Shoes (1948).

MANSEL STIMPSON

Featuring Martin Scorsese.

Dir David Hinton, Pro Matthew Wells and Nick Varley, Ex Pro Martin Scorsese, Ph Ronan Killeen, Ed Margarida Cartaxo and Stuart Davidson, Music Adrian Johnston.

Ten Thousand 86/Ice Cream Films/BBC Film/Screen Scotland/Sikelia Productions-Altitude Film Entertainment.

131 mins. UK. 2024. UK Rel: 12 May 2024. Cert. 12A.