The Damned Don’t Cry

Fyzal Boulífa’s second feature, a mother-and-son drama set in Morocco, once again shows that Boulífa is a better director than writer.

When Fyzal Boulífa’s first feature Lynn + Lucy appeared in 2020 it was highly acclaimed and I myself thought it a very promising work. At the same time, I did regard his directorial skills as being stronger than his screenplay, sensing that among other weaknesses it did not persuade you that Boulífa was entirely certain where he wanted to take his story. Now we have his second feature, a work very different from its predecessor. Nevertheless, I once again acclaim the filmmaking while finding the writing open to much the same criticisms as before.

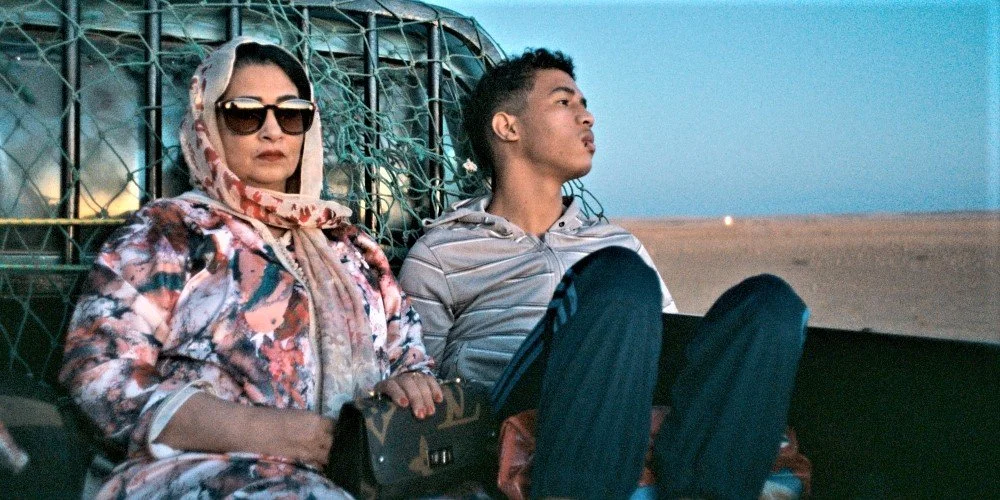

If The Damned Don't Cry is utterly different from Lynn + Lucy that can be attributed to the fact that Boulifa although born in England (the earlier film was set in Harlow) is the child of parents from Morocco which provides a setting for this new work. The main location is Tangier and the two leading characters are Moroccans played by non-professionals so it is not in the least surprising that the flavour of this new subtitled film should reveal a side of Boulífa not shown before. He elects to tell the tale of a mother and son. She is Fatima-Zahra (Aïcha Tebbae), a woman particularly close to her son, and he is Selim (Abdellah El Hajjouji) who has reached the age of sixteen. He has never known his father but quite early on in the film during a visit to his mother’s family he overhears her referring to the fact that his birth took place consequent on her being raped. This comes as a shock to him but his relationship with Fatima-Zahra has always been unusually close (at times it even carries a certain sensual charge) and the discovery does not change this.

The early scenes in The Damned Don't Cry strike one as especially assured. That applies not only to those with the family but to the preceding section which so adroitly establishes the character of the mother, a sensual woman now in middle-age who has always been ready to earn money for herself and her son through prostitution. There is no less conviction when mother and son move on to Tangier after the visit to Fatima-Zahra’s parents has led to heated exchanges particularly between her and her sister. Once in Tangier, we soon discover that, if Fatima-Zahra is herself leading a double life (she gives her son the impression that her assignations are actually job interviews), Selim too is doing the same thing. Taking on building work in Tangier leads to him being set up to satisfy the needs of a well-off gay Frenchman, Sébastien (Antoine Reinartz), and we then realise that Selim himself is gay although he hides this from his mother. As the film proceeds it follows both protagonists and shows how their lives increasingly start to diverge. Fatima-Zahra decides that her age is now such that she should seek a more respectable life and she seriously considers an offer from a bus driver (Moustapha Mokafih) who wants her to become his second wife. In contrast, Selim is ready to be employed by Sébastien and to settle into a close relationship with him but then faces a betrayal.

In telling this tale Boulifa adopts a tone that intentionally echoes film styles that he admires. One unexpected example of that lies in the title he has selected for this film: it is not by chance that it was also the title of one of Joan Crawford’s lesser-known movies made in 1950 and that choice is intended as a pointer to Boulifa being an admirer of melodramas. That does not mean that this film altogether embraces that mode although it is the case that Caroline Champetier’s photography does sometimes feature colour designs that invoke the Sirkian stylisation that Fassbinder brought to Fear Eats the Soul (1973). For that matter there is something reminiscent of the work of Tennessee Williams in the character of Fatima-Zahra, believable yet also somewhat larger than life and very much the figure who dominates the film. Aïcha Tebbae’s quite wonderful performance gives her a strength that prevents her from coming across as a victim of life. Hardly less potent is the music score by Nadah El Shazly which, despite sensing the melodramatic mode, nevertheless adds to the film’s atmosphere in a way that cements its authenticity.

If Tebbae stands out more than Abdellah El Hajjouji that is not because of any weakness in his acting but because Bouliaf's screenplay leaves us uncertain what we should make of Selim. Indeed, when The Damned Don't Cry reaches its conclusion one is left unsure what we are meant to feel. The splendid characterisation of Fatima-Zahra aside, the film’s main achievement is to paint such a convincing picture of a country in which attitudes to sex and sexuality encourage people to live double lives. That was also a feature of the Pakistani film Joyland made by Saim Sadiq in 2022 and in that case, regardless of any minor reservations, one knew exactly what the film was saying and admired it greatly. Despite the good things in it which continue to make Fyzal Boulifa a director to watch, The Damned Don't Cry is not its equal.

Original title: Les damnés ne pleurent pas.

MANSEL STIMPSON

Cast: Aïcha Tebbae, Abdellah El Hajjouji, Antoine Reinartz, Moustapha Mokafih, Walid Chaibi, Sawsen Kotbi, Samira Offeriche, Naima Louadni, Adelkrim Tarda, Souad Charaf, Ikram Elamghari.

Dir Fyzal Boulifa, Pro Gary Farkas, Clément Lepoutre, Olivier Muller and Karim Debagh, Screenplay Fyzal Boulifa, with Rungano Nyoni and Gabriel Gauchet, Ph Caroline Champetier, Art Dir Samuel Charbonnot, Ed François Quiquere, Music Nadah El Shazly, Costumes Cécile Manokoune.

Frakas Productions/Proximus/Kasbah Films/Vixens/BBC Film-Curzon.

110 mins. France/UK/Morocco/Belgium. 2022. UK Rel: 7 July 2023. Cert. 18.