‘Children of the Wicker Man’ Filmmakers Justin Hardy, Dominic Hardy, and Chris Nunn

by CHAD KENNERK

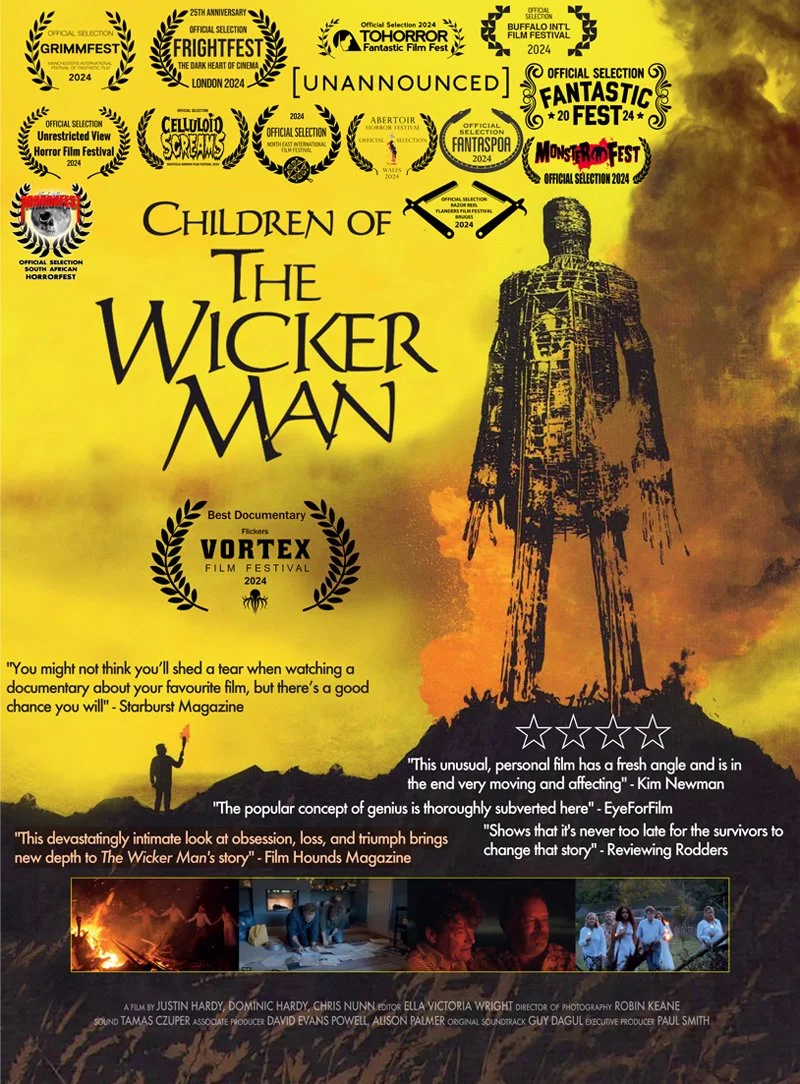

When six sacks of contents arrived courtesy of a mystery benefactor, filmmakers Justin and Dominic Hardy, sons of The Wicker Man director Robin Hardy, discovered an archive of lost papers, documents and personal effects relating to the making of their father’s seminal 1973 horror cult classic – a film that quite literally tore their family apart. Robin Hardy’s obsession with his directorial debut led to significant personal and financial sacrifices, leaving a mark on his family. Understandably, the brothers developed a complex relationship with their father’s work and the legacy of The Wicker Man.

The lore is legendary – from the beleaguered production, to its disavowal and harsh editing at the hands of distributor British Lion. An initial financial failure, the film remarkably saw a revival, often attributed to a 1977 commemorative issue of Cinefantastique, which called it "the Citizen Kane of horror movies.” It eventually reached the heights of cult classic status and found a permanent place in the halls of horror.

As The Wicker Man celebrates its 50th anniversary year, the documentary Children of the Wicker Man explores the origins of the celebrated independent film and the fraught relationship of the two men behind its creation; Robin Hardy and Anthony Shaffer. Setting off on a pilgrimage to follow in their father’s footsteps, the brothers discover the larger story through uncovered sources and newly harvested interviews. In tracing one of cinema’s beloved anomalies, the brothers find themselves at the apex of a deeply personal journey.

In conversation with filmmakers Justin Hardy, Dominic Hardy and Chris Nunn.

Film Review (FR): Children of the Wicker Man combines the personal and the professional in a way that we don't often see. What was the genesis for this project?

Justin Hardy: I really didn't wish to go near The Wicker Man, which I suppose is quite a useful beginning. I didn't contrive it; I simply didn't hugely like the film. I didn't really understand why I didn't like the film, and now I have a better understanding of it. The genesis of this film, quite literally, were six sacks of letters being sent to me by this lady saying that she had them and me going, ‘Oh Christ, I really don't want to go there and I certainly don't want to go there by myself.’ Then I called up Domi as a sort of supporting sibling. I'm so glad I did, because we literally went on this journey together. The fact that we're different, the fact that we had different attitudes towards dad, the fact that we had different attitudes towards the film and the discoveries that we made, really benefited that whole process. I think if I'd just done all that by myself, I probably would have ended up, you know, at the bottom of a bridge.

(FR): Research is something of a treasure hunt. How did you start diving into these sacks, and when did you decide to document the journey on film?

Justin Hardy: Domi will have plenty to say from his side on this, but as a documentarian, it is very rare to come across such terrific primary source material. We opened the six sacks – four of the sacks had crap in them, let's be clear about that. But with two of the sacks, we pulled out things like an original script for The Wicker Man. We then pulled out a second original script, and that one had ‘Robin Hardy’ in it, with a drawing by him. I mean, this really was breaking through into Tutankhamun's tomb. We found an original recording from De Lane Lea Studios. We then found letters that said, ‘Who are we going to cast?’ ‘Tony, will you let me direct this?’ ‘British Lion, Will you please stop recutting this film.’ The stuff in there was absolutely extraordinary. Do you agree, Domi? Wasn’t it mad?

Dominic Hardy: Mad indeed, yeah. It was also extraordinary for us in different ways, because this is a part of our life where we were at different ages, living in different continents, and suddenly here's all these traces of our dad's activity. We would have been too young to even understand what that activity was at the time. As the film goes on, we reveal more of what is the impact of our father's behaviour – as a business person, as a filmmaker, in his life – and its impact on us. We now had traces of all the mechanisms, of all the ways he behaved in the world with his film and business associates. Finding his handwriting, you can practically hear his voice from the time.

Justin Hardy: If I could clarify that for Chad, what do you mean by that? Do you mean that dad's aggression was evident? That his lack of loyalty was evident? His tempestuousness was evident? What was evident to you?

Dominic Hardy: The anger from time to time, but also the seductive approach, I would say. He would bring up his points and defend them, because he had a position to defend, but he would go out of his way to make a spectacle out of what his position was, and yet he created a space in which the people he was talking to still had a place as well. He was furious with Michael Deeley and Barry Spikings, for example, but he still managed to write to them practically, as though his life depended on it – certainly because the film depended on it. It's a glimpse into our father at work every day, every month, defending this project and defending his place in it.

Justin Hardy: Now are you saying that he's seductive, as he's seductive towards all the women in his life? Is he seductive towards everyone in making a film? Is he just so sex mad that he deals with everything in that way?

Dominic Hardy: He's survival mad, is what he is. That is probably part of all of those other emotional attachments that he has. It's his way of staying in the game. It was incredible insight into his personality from a professional angle. As much as we saw him involved in other projects over the decades, we've never had a glimpse like this.

(FR): I want to ask about the De Lane Lea studios recording and the music of The Wicker Man.

Justin Hardy: The music of Wicker Man lives on in many ways beyond the film. What we discovered, and something we couldn't quite make room for [in the documentary], is that there was a whole sequence in the film that came out – confirmed by the music contributors – which was a dream sequence where Howie, having been drugged by the hand of glory, has a dream about everything that's gone on in the film. He starts to realise that there's a game being played, but he doesn't quite put the final pieces together. He then manages to break out of that nightmare, smother the hand of glory, and heads off to go and join the procession. That would have been a very good scene and apparently the musicians tell us that they recorded music for that scene, that critical turning point in the film, and they are so sad never to have heard it since. They don't know where the recording went and that's a great loss to The Wicker Man fan world.

(FR): There's so much packed in the documentary, but I'm sure there's so much more that you didn't have space for. What were some of the things that didn’t make it into your final cut?

Chris Nunn: With the source materials that we had and the kind of lore around The Wicker Man, there were probably a hundred different films that could have been made from this stuff. As was mentioned, I think in our Q&A at Fantastic Fest, we are working on a second documentary, which will be much more about, not just the making of The Wicker Man, but why it still stands the test of time 50 years later. That's probably the film that we started making, but of course, as you've mentioned, the letters and the original source materials that we found — a lot of that was very personal. We do feel, the three of us as academics and historians, that actually we did follow the sources, just maybe in a way that other people might not have.

So we lost material on De Lane Lea and the music – we had a whole sequence about that which we decided to take out, because we didn't have room. We had a lovely and hilarious six minute sequence on the mystery of Britt Ekland’s replacement bum, which continues to be a mystery, even 50 years later. I think we identified four different women who had claimed they were the bum or were said by Robin Hardy or Peter Snell or Anthony Shaffer to have been the mystery bum. That's a hilarious piece of Wicker Man lore. We did a really hard pass of one of our final cuts and we just had to say, ‘Is it about the brothers? Is it about Robin Hardy? If it's not about either of those things, we might have to pull it out.’ So brace yourselves for a hilarious six minute sequence on the missing Britt Ekland bum that will come in Wickermania! for sure.

(FR): Christopher Lee’s presence obviously looms large over The Wicker Man and over this documentary as well, because of all of the personal appearances that Lee and Robin Hardy made after the cult status of the film. What were your perceptions of Lee and his legacy?

Justin Hardy: I got to know Christopher pretty well. Christopher Lee was in the first film I ever made called A Feast at Midnight. He wouldn't have done that if he hadn't done Wicker Man, so I'm very grateful for that. I'd worked with him a number of other times. He became a family friend and I was one of the people that lobbied for him to get a knighthood. And when he got it, he never stopped bloody going on about it, so I wish I hadn't. It's really only fair to say, he was one of the world's most annoying and boring men. His stories were legendary. They went on and on and on. According to Edward Woodward, Lee would literally turn up at any given scene and start telling a story about a golf course. He had 18 holes to get through, each of which was elaborately described, and he could pick up the story at any moment. Woodward was an actor who needed to believe, needed to remember his lines, needed to get into the part, but Christopher wasn't like that. Christopher could switch on and switch off.

For Wickermania!, we've got this whole sequence of a designed Christopher going around and saying, “And so, on hole number four, I think you'll find it's got quite a strange fade that leads to the green.” That's part of the fun that Wickermania! is going to be. You asked how Chris was, he was a very, very long winded, self-start storyteller. But, and dad made this really clear, he was one of the most loyal men he ever worked with. Christopher's loyalty was legendary, and his loyalty was to The Wicker Man. He originated it. He kept pushing it. He was in so many other films. Why on earth bother about this little indie, quirky film? He did and he did it to his dying day.

(FR): What has following in the steps of The Wicker Man meant to each of you? We saw a lot of it in the documentary, but having had a little distance from that experience, what are your thoughts now?

Dominic Hardy: Following in the footsteps of dad, standing in the footsteps of dad on the cliff sides of Burrowhead where The Wicker Man was filmed, is the moment where the film came home to me after all those years. At 12 years old, I was taken to an early screening before it was even edited and chopped and bowdlerised. I saw the Cinefantastique magazine, but all from afar. It was a major presence in our lives, but it was a presence ‘over there’. I realised when we were making this film that I never really formed an aesthetic opinion about it. I'd never really gotten to the heart of it or cared for it in a deep way. In making this film, especially in going to Scotland, it sort of washed over and into me. ‘Oh my god, this is what this film was about.’ It just made it real. I remember saying to Justin, “Isn’t this interesting that we're sort of in our late 50s, early 60s, and we've never come here.” It had never occurred to me, ‘Oh, I must go up to Burrowhead sometime and see where dad made this film.’ It was just locked away. The Wicker Man became a reality in making Children of The Wicker Man.

Justin Hardy: I'm glad to say that this film was sort of a passage through our father in order to reach my mother. I am very grateful for the opportunity to have unearthed and surfaced her contribution to the film, which was one of the reasons why I'd always been so very sad about the film. Now I'm able to put a positive slant on it, in that I'm able to register mum in a much more positive light. She never knew that it was a hit, having literally given up her entire life and love for it. I was recently awarded a posthumous accolade at FrightFest for her and in her name. We're going to now create our company to make our future films in her name.

Chris Nunn: There's two things, actually. The first is a natural curiosity. Justin and I had very early conversations about The Wicker Man as we were lecturing together in London. One day I said to him, “Don't you understand the appeal of The Wicker Man? Don't you get it?” Obviously, now I understand quite why he didn't want to understand the appeal of The Wicker Man. I don't think our film quite addresses it, but I do think in the sort of wider project and all the things that we've amassed, that I've come closer to understanding a lot about it. In a more practical way, going to Scotland and following literally in the footsteps of the crew who made that film, I've realised how bonkers that shoot was. I mean, these guys were absolutely nuts.

Summerisle, as a construction, I've always thought was a cinematic piece of genius, because I've never, ever questioned that Summerisle is not an island. Easily, the first few times I watched that film, I went looking for Summerisle thinking, ‘Oh, they obviously just got on a plane and found this island.’ Now I know it's a construction of 50 miles of various locations. It's nuts. No wonder they had such a tough time filming it, because they were constantly travelling from place to place to place. We did land in Kirkcudbright, which is one of the main towns that they used, and sort of looked around and went, ‘Well, this probably would have done it.’ It would have worked just fine, with a few hops outside. As you tour those towns in that corner of Dumfries and Galloway, you say, ‘Oh that's the library. Oh that's the church. That's the outside of the pub.’ I'm sure this could have been done in a simpler way.

(FR): Do you think that came from it being his first film? He had a very experienced crew.

Chris Nunn: I'm struggling to know where it came from and who would have made those decisions. I mean, we know your dad went up on a few recces?

Justin Hardy: I think it does come down to dad's naivety. I think that he thought as a commercials guy, where there's quite a lot of money on offer, and every location is then very, very specifically thought about. In the greater context of the movie, it would not have mattered if the locations had all been in one town. To him, the camera mattered, the production design mattered, and the extra few percent [added by the locations] really mattered. The Wicker Man is not great because of that, it’s great because the music's great. It's great because the cast is so bonkers. It's great because Anthony Shaffer’s script is really tight and you really want to know what's happened to the girl. I think that dad and the production designer were all pointing their guns in the wrong direction. Luckily, it did not ultimately flaw the film. But it is not a template of how to go and make a film.

(FR): What are your thoughts on the legacy of The Wicker Man?

Chris Nunn: I think the way that we're trying to approach it in the subsequent documentary is a combination of interviewing the survivors who were involved in the making of The Wicker Man, who can help articulate more stories, but also academics and intellectuals who talk about the themes of the film and why the film resonated with audiences when it finally got revived and recognized and why we’re still talking about it 50 plus years later. You might first go, ‘Well, The Wicker Man's famous, because isn't there that rumour about it being buried under the M3 motorway? And isn't it that Britt Ekland’s bum isn't actually Britt Ekland’s bum? And didn't they shoot in winter, but it's actually spring?’ Initially, you think this is the lore that grants it cult status, but actually, when you start talking to other academics and critics about the film, you discover that its themes are resonant and have resonated. This is confirmed by anthropologists, neuroscientists, folklorists and real pagans, as much as it's confirmed by film academics.

Justin Hardy: Added to which, is that big stars love it. Quentin Tarantino, Simon Pegg, Nick Frost, Guillermo del Toro. You could throw a stone anywhere in Hollywood and hit somebody that would say that Wicker Man was really inspirational. With this documentary, we intend to go to Hollywood and kind of crash into various restaurants and ask people what they think, because we probably won't be able to arrange a meeting.

(FR): Guillermo loves to talk about film. Tarantino too, for that matter.

Justin Hardy: I think that's right. I mean, I think that we're pushing against a reasonably open door. I think that the film's going to have that bit of star power. With this little film, Children of the Wicker Man, we were aware that we were taking a lesser fork in the road. We were aware that we were making a film that was personal and that we were leaving a lot of material to be made into a subsequent film that would be a bigger, jollier splash, but I would suggest – and I think I already get the sense from you – that you appreciate that we made this personal version, because people don't. They don't do this. I think we've been a bit radical.

(FR): There are universal themes and aspects that everyone can relate to. This project and this process seem to have been helpful for you, simply as brothers. You mentioned your production company and continuing to tell stories together — it's blossoming into a closer collaboration professionally.

Justin Hardy: Our project, apart from Wickermania!, is that we are going to be making a fiction feature film, which is very much of our own concept. Domi and I have written the story and I've written the screenplay and Chris is gonna be producing. It springs off from Wicker Man, rather than being a sort of a sequel to Wicker Man. Dad did, as he was dying, kind of point his bony finger on the map up to the other parts of Scotland, which leads out into the North Sea towards Norway. We went to the Shetland Islands and they said, ‘Oh yes, your father was here.’ So we said, ‘Well, what did he want to talk about?’ What he wanted to talk about was making something about the Norse pagans, the paganism of the Vikings, etc. We took him up in a plane to show him an island, but unfortunately he fell asleep. So there's this sort of lost idea of Robin Hardy that we are completing and we're shooting that in the Shetlands in the spring. Domi, meanwhile, has got The Wicker Chronicles, which are coming from the Wicker world, but are graphic art [based], because Domi’s an art historian.

Dominic Hardy: There's a book already on the threshold of being sent to the publisher. We've written a book to go with the film, which allows us to go deeper. There are so many issues raised by The Wicker Man which speak to the past. There's some things that are alluded to — Victorian ideas about science, nature and the Gulf Stream. Our idea is to actually go back to Lord Summerisle’s origin story and look around in the 19th century in Britain and see what the ideas and mysteries might be that led the grandfather to go to that island in the first place. The Wicker Chronicles will expand and investigate the world that is still alive on Summerisle in the early 1970s and which has so many lessons about climate change. The story about the apples, for example, you can relate that very, very closely to the changes that have been going on through the 19th and the 20th century. It's all happening in the crux of the industrial age.

Justin Hardy: Basically, we intend to keep wickering on, don't we?

JUSTIN HARDY is a multi-award-winning historian filmmaker, having won the first ever Royal Television Society award for best historical film in 2001, and since then won three times more. He has been nominated for Bafta and Emmy twice and won numerous other international awards for his work that has spanned drama and documentary. His feature documentary, The Green Park (2016) won two major international awards, including The London Independent and Monaco Film Festival. Justin has worked for a variety of channels: BBC, Channel 4, ITV, ARTE, PBS, Discovery and CNN, directing actors such as Sir Lenny Henry, Sir Christopher Lee, Sir John Mills, Amanda Redman, Olivia Williams, Iain Glen, Ian McDiarmid, Roger Daltrey, Sunetra Sarker and Geraldine James. In 2022, he was awarded a PhD in history and film, in which he defined for the first time the genre created within historical drama-documentary. He teaches at UCL across both film and history, designing three new programmes for BA Media, Creative Arts and Humanities, and Public History, situated in the new campus at UCL East.

DOMINIC HARDY is the executor for the Robin Hardy estate. He is Professor of Art History at UQAM in Canada, specialising in political cartoons of North America and Europe since the 18th century. He is also the film’s illustrator, and will be creating an original art print based on one of his father's drawings for Children of the Wicker Man’s executive backers.

CHRIS NUNN is an assistant professor of film at the Russell Group University of Birmingham (top 20 in UK; top 100 internationally). His research specialises in filmmaking education, and former students have gone on to win at the BAFTAS and RTS, as well as be nominated for Grierson and student Academy Awards. His research extends into cult film and television.