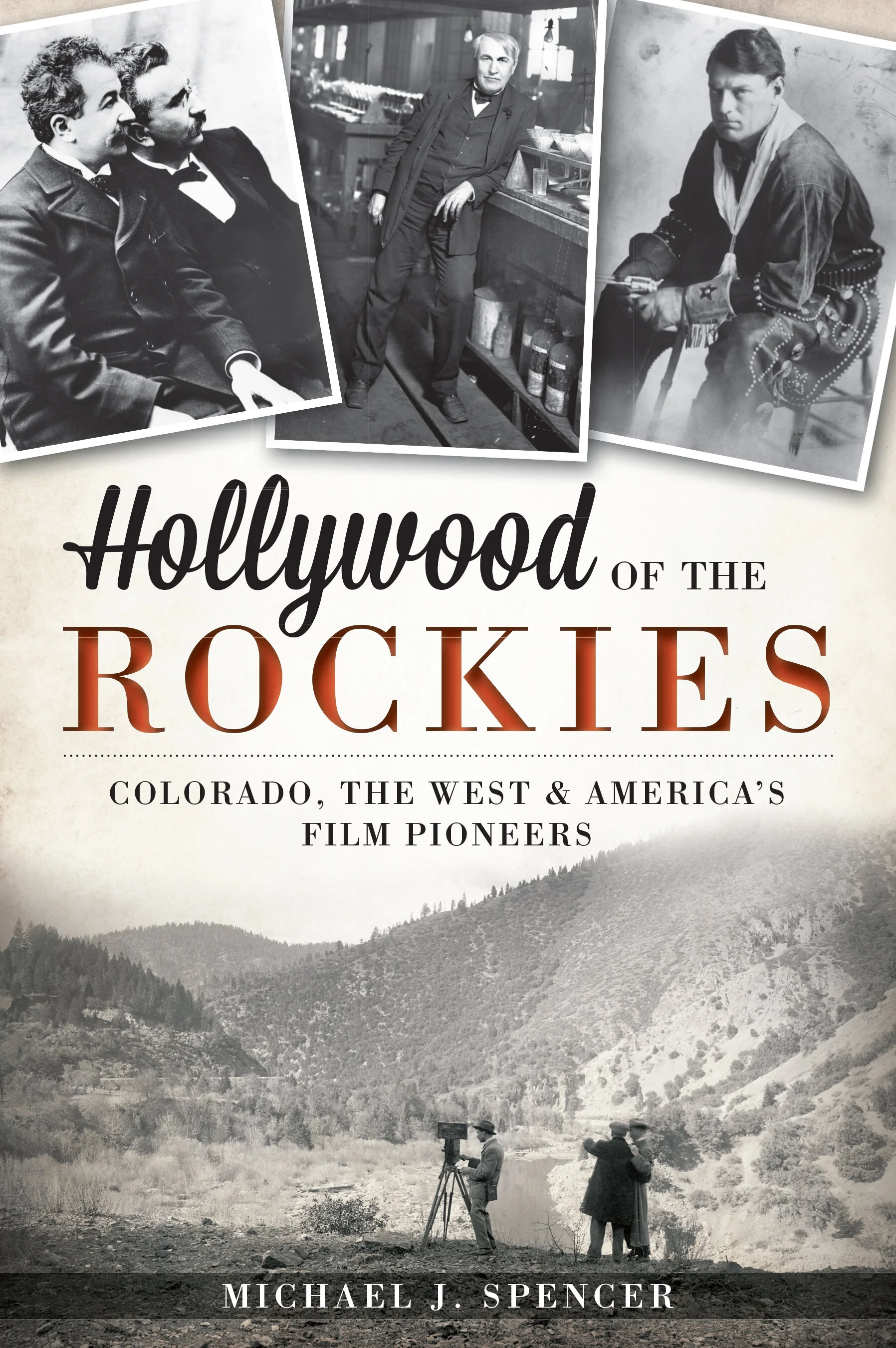

Hollywood of the Rockies

by CHAD KENNERK

Film Review chats with author

Michael J. Spencer about America’s film pioneers and pre-Hollywood silent films shot on location in Colorado — a subject richly researched and detailed in Michael’s fascinating book,

Hollywood of the Rockies.

In conversation with author Michael J. Spencer

Film Review (FR): Hollywood of the Rockies details the journey of American film pioneers as they traveled westward. In many ways, this feels like a previously unwritten chapter in the history of film. Most texts tend to skip from New York to Hollywood. How did your original PBS documentary come about and what inspired the book?

Michael Spencer (MS): It all started when I was putting together a proposal for a film project several years ago. I can’t quite remember what it was and to be honest, I think it was just some cheap exploitation thing like a martial arts film. I was in the Western History Department of Denver Public Library looking for information on recent productions that had filmed in Colorado, just some random facts to prove that filming was not unheard of in the state. I was mostly looking for financial figures.

I stumbled on an entire box filled with photos and ephemera from movies that had been shot in Colorado before World War I. This was something completely new and I was fascinated. I started doing research on this new topic and found there was a completely forgotten slice of American film that had slipped through the cracks of public consciousness. I dropped the other project (easy to do) and put together a proposal for a documentary to tell the story of early filming in the Rocky Mountains. Ultimately I pitched it to Rocky Mountain PBS and turned it into a documentary.

Years later a friend of mine who had had a history book published introduced me to his editor and the result was a plan to create a book inspired by the documentary.

How do you turn a film into a book? That’s sort of the reverse of how it’s normally done. The first – and completely practical - difference I realized was that the narration for the documentary script was about 3,000 words and the book would have to be closer to 35,000 words. A simple transcription of the script wasn’t going to cut it. So the good news was that I’d be able to really go into a lot more detail about the lives of the people and the particulars of the events. The bad news was – I had to write 35,000 words.

FR: The West and particularly the 'Western' genre were key elements in the formation of the film industry. How did Buffalo Bill, Thomas Edison and the Chicago World's Fair lead us from West Orange New Jersey to the American West?

MS: Buffalo Bill was at the forefront of the media phenomenon that the ‘the West’ had become by the end of the nineteenth century. He wasn’t the first, the only, or the last – but he was certainly the best known of those who romanticized the West and capitalized on it. As such, he helped increase the popular appetite for all things western and that appetite fed immediately into films. He and his wild west show actually made appearances in a few films of the 1890s and early 1900s but he was, by that time, a little long in the tooth to exploit it fully himself.

Thomas Edison - aside from being one of the inventors of moving pictures and certainly the popular face of it throughout the world – wasn’t too involved with the production of the films themselves. As Gilbert ‘Broncho Billy’ Anderson later said, Edison wasn’t very interested in the content of his films, he was just fascinated with the technical aspects.

But the Edison Manufacturing Company produced and distributed a number of western films, notably The Great Train Robbery, the film that drove the attraction for western films to a full gallop in 1903. It had cowboys, it had chases, it had guns, it had horses, it had barrooms. It was the public’s enthusiasm for westerns such as this that sent filmmakers westward, searching for authentic locations.

There is some speculation that Edison’s Kinetoscope made its debut at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. But by all accounts (even, implicitly, by Edison himself) the machine was not there. I think the confusion comes from the fact that the company had hoped to unveil their creation at the Fair and had heavily promoted it. But the magic machine was barely out of the lab stage and production simply hadn’t geared up fast enough to produce enough Kinetoscopes and – importantly – enough filmed content in time for the opening of the fair.

There were a couple of relatively simple moving-image-type machines at the fair. Eadweard Muybridge was demonstrating his Zoopraxoscope and a German, Ottomar Anschutz, had his Electrotachyscope. Both of these used a rotating disc, rather than film, to give the illusion of movement.

FR: Former Film Review contributor and cinema’s most recognizable cowboy, John Wayne, briefly ran into another famous film cowboy at the beginning of his career — Tom Mix. Who was Tom Mix and fellow motion picture cowboy Gilbert Anderson?

MS: I like to look at it this way: Gilbert Anderson was a showman who decided to become a film cowboy and Tom Mix was an actual cowboy who decided to become a film showman.

Tom Mix started out working as a ranch hand in the West. When he began performing in movies, he glamorized it and played the part of a romantic cowboy to the hilt. In interviews, on the radio, he was Tom Mix the character, so much so that you feel like he might have believed he actually was ‘movie Tom Mix’ in the flesh. Gilbert Anderson harbored no such illusions. He joked about how he couldn’t ride a horse – but he was pretty good at acting like he could.

FR: It’s difficult for us to comprehend today just how many films were made in Colorado during these years and that’s largely due to the value of the film stock. Can you speak to that and do you think film history might be told somewhat differently if more films from the silent era existed today?

MS: Most silent films, whether made in the Rockies, the East or California or elsewhere, are lost to us so it’s not just the Rocky Mountain films that are missing. It’s hard to say how radically different film history might be viewed if some or most of those could be restored since, really, most of our sense of history comes from first-hand accounts along with articles and documents of the times.

There would probably be a few shifts in who did what first. You know: “Ah-HA! The first use of parallel action actually occurred two months earlier than previously thought!” So the restoration of these films would probably add nuances to history.

I think that, more than our perception of history, these lost films would expand our aesthetic understanding of early films.

FR: What was your research process for the book like and what were some of your largest discoveries along the way?

MS: Once I dug into it, I moved far afield from the material that originally inspired me in DPL’s Western History Department. Particularly with the book (more so than the doc), I decided that I wanted to tell the larger story by putting it in the context of the entire American film industry - since that’s the context that the participants were living in.

I took the same approach you’d take in putting together a novel. I introduce a few interesting characters – in this case they happened to be real people – characters with talent, characters with flaws, characters with hubris. You know how novelists say they set the characters down on paper and then the characters take over and do whatever they want. Suddenly the story is going in the direction the characters want and not necessarily what the author planned. That sort of happened here – but of course, these characters have existing facts about them. And fortunately, it turned out that what the characters in the book wanted to do ended up being what their real counterparts did in real life.

FR: Was it difficult to secure images for the book or were many in the public domain? Can you talk about working with resources such as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Margaret Herrick Library?

MS: The original doc was loaded with film clips which I’d gotten through the Library of Congress and several other sources. When viewing these films and actually seeing these archaic moving images, you get a visceral sense of what it might have been like watching them for the first time over a hundred years ago. No matter how often I see them, I still feel a sort of aching sense of wonder.

But, of course, you can’t do that in a book.

Once I started putting the book together, I realized that I’d have to replace and supplement all of that with still images. I couldn’t just use freeze-frames from the films. If you’ve ever tried to grab a still from a motion picture you know how unusable that is for the print medium. And the photos in that box in Western History, though inspiring, were hardly enough to fill a book.

So I began the process of tracking down other sources for additional production stills and historical photos - from tiny municipal museums to huge, world-class institutions.

I can name a few. The Museum of Modern Art, History Colorado, Western History at Denver Public Library, the Lumière Institute. And a completely esoteric research center and showcase: the Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, housed in Niles, California, once home to Broncho Billy’s Essanay Studios.

People often ask about working with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Margaret Herrick Library. It’s an incredible place, stuffed with film-related one-of-a-kinds you won’t find anywhere else. (Of course!) The people are professional, they’re knowledgeable and they’re friendly – but I’ve found you can say that about just about every librarian and research assistant anywhere.

The building itself is pretty amazing. The library is housed in what was once a municipal waterworks in Beverly Hills – a beautiful Spanish Colonial structure built in the 1920s. And since it once accommodated all that waterworks equipment, the interior is very airy and spacious. It’s very relaxing working there.

As far as securing the rights to use the images in the book, each organization has its own rates and restrictions. Keeping track of all these usage rights and fees was a major undertaking in itself.

FR: With initiatives such as the Colorado Film Incentive, do you think we’ll see Hollywood truly return to the Rockies?

MS: There are many, many, many variables that people take into account when choosing a film location. Yes, money - and film incentives - are absolutely near the top of any list. The competition is fierce. We’ll have to see how much the Colorado Film Incentive sways filmmakers to shoot in the Rockies.

FR: Of all the films subsequently shot in Colorado, what films rank among your favorites?

MS: They say parts of The Searchers were shot in Colorado but I think it was only second unit work. In any case, it’s certainly a great film and one of my favorites. And you can’t argue with a movie that has a building named after it – the Sleeper House in Genesee, Colorado.

Filmmaker and writer MICHAEL SPENCER started his career with a modest little film called Helium! a movie studying the life of a once-happy balloon gone bad. This send-up of The Red Balloon was chosen to represent the changing face of independent film at the Foundation for Independent Video and Film in New York City.

His award-winning documentary, Hollywood of the Rockies, the story of the westward journey of America’s early film entrepreneurs, became the basis for his non-fiction book of the same name. The Library Journal called it “ . . . a fast-paced, humor-filled, romping read.”

His film work has been a part of programming for PBS, A&E, the International Television Association, USA Network, Comcast, the Library of Congress and others. He’s won awards at the Chicago International Film Festival, Worldfest, Moondance, CINE Golden Eagle, Emmys and Cinequest among others.

Learn more at: http://www.hollywoodoftherockies.com/

CHAD KENNERK