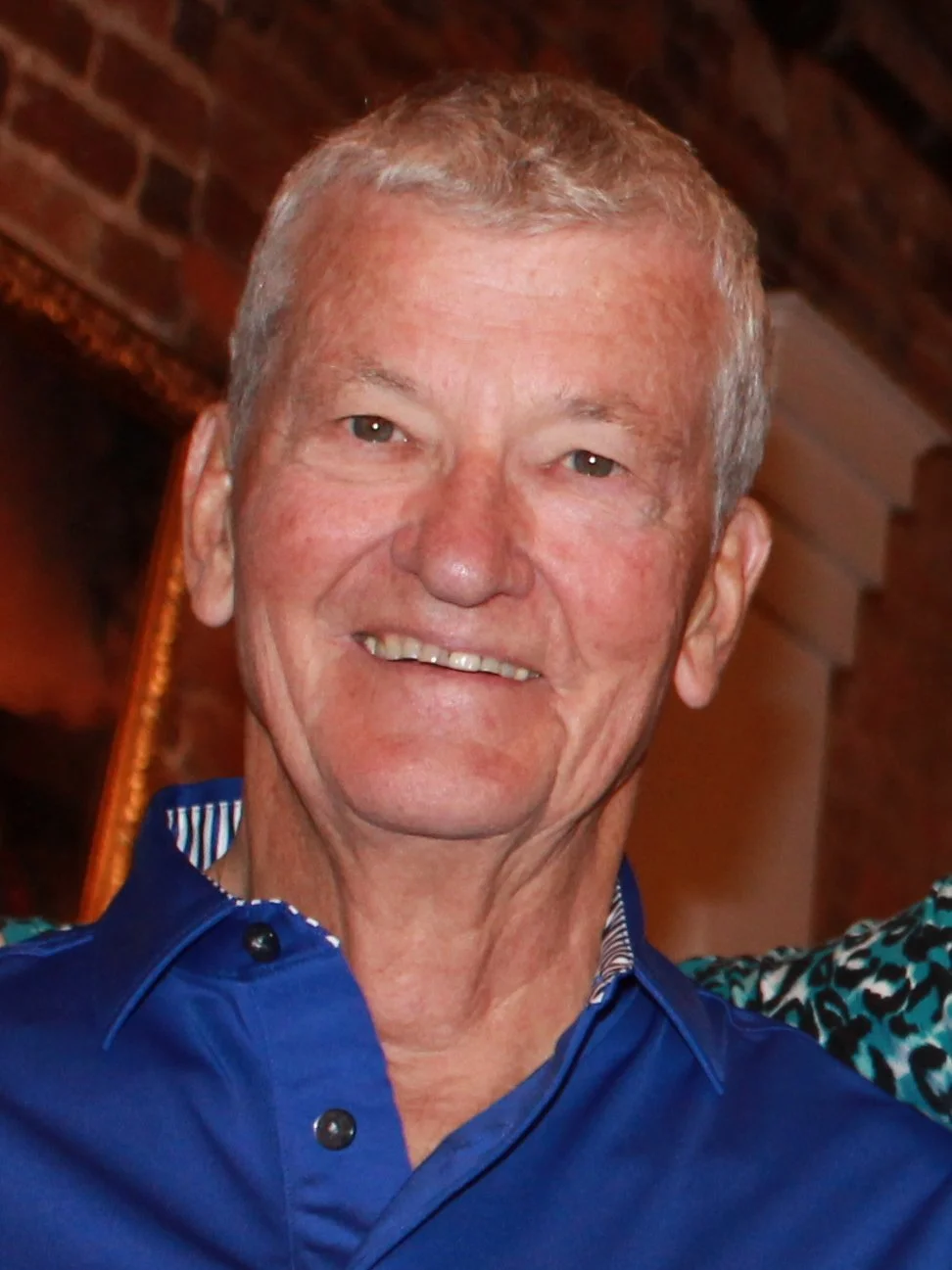

Mickey Kuhn

Mickey Kuhn. Image: The City of Marietta, GA

Stars of the Golden Age

by CHAD KENNERK

The late Mickey Kuhn began his movie career at the tender age of two in a 1934 film that featured another rising child star—Shirley Temple. Throughout his career Mickey appeared alongside scores of Hollywood legends and held his own acting opposite them. His role as Beau Wilkes in Gone with the Wind cemented his cinematic legacy, which grew with further roles in classics such as Red River and A Streetcar Named Desire. Film Review had the great privilege of speaking with Mickey prior to his passing. He was a genuine presence, humble in nature, full of enthusiasm and a wealth of stories. When we asked if he ever thought about compiling his stories into a book, he said, “I’ll tell ya, If people enjoy hearing them, that’s all I care about. I enjoy relating them.”

In conversation with Mickey Kuhn

Film Review (FR): Your family moved to Southern California in 1934. How did your journey as an actor begin?

Mickey Kuhn (MK): We were originally from Waukegan, Illinois. I was born there. Jobs weren’t to be had then. My dad was a meat cutter and he found that there were job opportunities in California, because the streets were ‘paved with gold’ in Hollywood. So we packed up and came out. We settled in an area of Hollywood that was kind of nice; Santa Monica Blvd and Western Ave. Both were commercial streets and on Santa Monica Blvd there was a Sears & Roebuck. We actually lived right behind the store. There were small single family homes, we called them courts in those days, a bunch of single family dwellings that were all in a complex. My mother was handicapped and she couldn’t walk very fast, but she would take me for walks. She liked to go into Sears and window shop, just something for a break. My father worked 12 hours a day, from seven in the morning until seven at night. Now, this is all what I was told second hand. I was 18 months at the time.

One night, we were in Sears and this woman came up to my mother and said, “Excuse me. You know, your baby looks just enough like my baby that they could be twins.” My mother said, “Yeah, and?” The lady said, “Tomorrow 20th Century Fox is having an interview for twins, they want to use them in a movie. Would you be interested in going out and we’ll try and tell them they look enough like twins that they could be?” My mother, who was always kind of a latent thespian, said, “Yeah, I’ll go.” So we went out. We were sitting there waiting in the casting office and this fellow came up and said, “This is the baby I want for my movie.” He took me out of my mother’s arms and off we went down the hall. His name was John Blystone and he was the director. My mother walked with a severe limp. I have a vision of her waddling from side to side at top speed going after this guy, until she caught him and found out what was happening. The movie that he was making was Change of Heart with Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, James Dunn, and Ginger Rogers. My wife likes to say it was my first and only adult movie, because my first appearance in the film was stark naked. I have to live that down, but that’s how it began.

(FR): With a nude scene!

(MK): Yeah, with a nude scene! From there, my mother pursued the opportunity. In 1937, I was in a movie called A Doctor’s Diary. It just kind of progressed. I was very fortunate to work at the time of the Depression. In 1938 on Juarez, with Paul Muni and Bette Davis, I made a hundred dollars a week. My mother and father thought they’d died and gone to heaven.

(FR): What’s the first film you remember working on?

(MK): I have memories of A Doctor’s Diary, I can remember what I did. I was in bed and John Trent came up and was talking to the kids. My line was, “Can I get up today Doc?” I can remember them pretty well. In fact, if I have a lapse in memory, I have 32 of the movies I was in. I remember Juarez pretty well.

(FR): What was that experience on Juarez like, working with Bette Davis?

(MK): It was an experience. Brian Aherne was very easy to work with and so were Harry Davenport, Gilbert Roland, and Donald Crisp. Bette Davis was very difficult. She didn’t like kids. She made that quite well known. She was the toughest I ever worked with. When I worked for American Airlines, which was the last 30 years of my working life, I was stationed in Washington D.C. Our offices were in the basement. All of a sudden, the word came down from upstairs, “Bette Davis is in the terminal. She’s travelling with us today.” I said, “Oh my, you know I worked with her in 1938.” My boss at the time didn’t know that I had a career prior to American Airlines. She said, “How do you know her?” I said, “I’ll tell you when I get back.”

So I went up and found her, she was older then and she was wandering around the terminal. No entourage, just her. I approached her and introduced myself and said, “Ms. Davis my name is Mickey Kuhn and I had the honour and privilege of working with you in the movie Juarez in 1938.” She looked at me and said, “Oh, how nice for you.” I thought, ‘Whoa, wait a minute, that’s not supposed to be the response!’ So I choked that down and said, “I’m now with American Airlines and I’m a supervisor of flight service. Is there anything that I might be able to do for you to make your trip from Washington a little smoother or a little nicer?” And she said, “No.” I said, “Oh, ok. Well if there’s anything I can do, you be sure to let me know.” And she said, “Ok,” turned around and walked away. You can imagine how I felt. First of all, I felt like I was intruding on her, which I certainly wouldn’t do, but boy, my attitude toward her changed significantly.

(FR): It probably took you back to being on set with her at six.

(MK): Right, and she was not nice at six! She was the most difficult. The best? The very, very best I ever worked with were John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart, and Walter Brennan. I’ll tell you who else was really neat was Anne Bancroft. She was a sweetheart.

(FR): What was the casting process like for Gone with the Wind?

(MK): You won’t believe it. I was working on a movie at Republic Pictures called S.O.S Tidal Wave. I’d worked a couple of weeks on it and we were wrapping it up, it was the last day. It was a bit intense, trying to get everything done and everything right. Out of an eight hour day, we had to go to school for three hours. We could either go to school at the beginning of the day, or during the day, but it was three hours. Not two hours and 59 minutes or three hours and two minutes, it was three hours. Those old broads were tough when they kept track of time. About three o’clock, just after I finished school—my mother said to me, ‘Now we have to leave here at four o’clock.’ At that time, Culver City was a big distance from the San Fernando Valley. There were no freeways. We had to go over a mountain range of hills and fight the traffic at that hour of the day to get out there. My mother said, “We have to be in Culver City at five o’clock. You have an appointment.” What do I say, except “Ok mom.” She said, “We have to be out of here no later than four-thirty.” I guess we must have gotten out there. My mother drove like Mario Andretti in traffic. We made it over and got admitted to the casting office. We walked in and I couldn’t believe it. It was filled with kids and parents. I bet there were a hundred kids there. I may be exaggerating, but it seemed like that. I turned and looked at my mother and said, “Please, let’s not. Why am I here?” She said, “You go and give your name at the casting office window and we’ll stay ten minutes. If you’re not called by then, we’ll walk out and leave.” I’m about ready to cry.

So I go up to the window and knock. A lady comes to the window and I said, “Hi, my name is Mickey Kuhn and I’m here for an interview.” I had no earthly idea what it was for. She looks at me and says, “Oh Mickey, thank God you’re here. Just a minute.” My heart sank. She was happy to see me. I was hoping it would be the other way around. I thought, ‘Well, there goes that ten minutes.’ She went and she got Marcella Rabwin, who was Mr. Selznick’s assistant. She says, “Oh Mickey, thank God you’re here, we’ve been waiting for you. Go get your mother and come right in.” So I went and got my mother and walked into the office. Marcella said, “Wait here for just a minute.” She sticks her head out of the window and says, “Thank you all for coming, but the part has been cast.” Closes the window and walks away. Now bear in mind, I had friends out there, fellow child actors. There were about ten of us in Hollywood at the time that did all the work, because we were ten different types. We just had a lock on it. We went into Mr. Selznick’s office. He and Victor Fleming were sitting there talking. We sat down and had the interview. Both Victor Fleming and Mr. Selznick chatted with me. What they said, I don’t have any idea, because I didn’t pay a bit of attention to it. I didn’t want to be there.

(FR): You’d had a long day on set.

(MK): Exactly and I was tired. So I sat there and did the best I could. Finally, at the end of the interview Mr. Selznick said, “Well Mickey, would you like to work for Mr. Fleming and me in our movie?” And I said, “Oh yes, Mr. Selznick, I would!” He says, “Well that’s fine. I think you’ll work with us and we’ll be calling you in about a week or so.” I said, “Thank you sir,” and walked out with my mother. It took about 15 minutes for the interview and that was it.

(FR): Did your mother realise the significance of that meeting? There was a lot of buzz around Gone with the Wind being adapted for film.

(MK): There was, but her big thing was about The Wizard of Oz, because that was going to be the movie of the year. Gone with the Wind was just something that came from a book that my mother enjoyed reading, but she had no idea — absolutely no idea—how big this movie was going to be. She never lived long enough to see me reap the benefits. She died in 1963 and at that time, all of the people involved in the reunions didn’t know where the heck I was. It wasn’t until the 50th reunion that I ‘resurfaced’.

(FR): What are some of your memories of filming Gone with the Wind?

(MK): There’s the scene where I’m sitting on the play room floor with Bonnie (Cammie King). Clark Gable comes in, picks her up and says, “I’m taking you to London.” I’m sitting on the floor and my line in that particular scene was, “Hello Uncle Rhett!” Now I have to admit, I was infatuated with that five-year-old little girl at that time. I found it hard to keep my mind on business. My simple line was “Hello Uncle Rhett!” That’s it. Three times he came in and it was, “Hello Uncle Clark!” Now bear in mind, they had three Technicolor cameras there. There were three available in Hollywood at the time and that’s what we shot with. We had the whole kit and caboodle there. At the end of the third attempt, Mr. Gable says, “Mick, come here.” I thought that was the end of my career, I’m through. He said, “You know, you’re right, I am Uncle Clark. But here in this scene, I’m Uncle Rhett, ok?” I said, “Yes sir, Mr. Gable.” So we shot it again, it was “Hello, Uncle Rhett.” and they used it. Now my crying scene was kind of interesting. That was filmed on April 29th, 1939. How do I remember that? I have the call sheet!

(FR): That’s a great piece to have!

(MK): I got to work early and they’d shot a couple of scenes before me. Leslie Howard kind of looked at me, picked me up and he said, “How do we make him cry?” Victor Fleming said, “Don’t you worry about it, I’ll take care of that.” Victor Fleming took me from Leslie Howard and we walked into what was Melanie’s bedroom. He just created a sad visual for a six-year-old. “How would you feel if your mother was really dying? At the same time, how would you feel knowing that your mother was dying and your dog got hit and killed?” Just to create a scene. I saw that picture and I started crying. He took me out, handed me to Leslie Howard, went behind the camera and said, “Ok, let’s go.” I heard the word ‘Action!’ We did the scene just one time. I heard ‘Cut!’, but I was still crying a little bit. I remember Leslie Howard looking at me and saying, “Now what?” Victor Fleming says, “I’ll take care of it.” So he takes me again and walks me back in what was meant to be Melanie’s bedroom. He started painting a picture of nice things to bring me down from crying. I was still sobbing a little bit and he says, “Mickey, would you feel better if you hit me?” And I said, “Yes, Mr. Fleming.” So I threw a left at him and just as I threw it, the photographer was there and he snapped the still picture. I still have it.

(FR): He got the shot and so did you!

(MK): That’s right. Then at the end of the movie, Mr. Fleming gave leather-bound signed scripts to each of the featured players. Unfortunately I wasn’t quite that featured, but he gave me a 16mm projector and movie camera to continue my movie career as I got older. I had that for years and years. The interesting story on that was, we got a call to come into his office to see him. We walked into his office and he had someone in there. It was movie star Joseph Cotten, who was quite handsome. I thought my mother’s heart would never stop palpitating. Mr. Fleming said, “Oh hi Mickey. Hello Mrs. Kuhn, of course you know Joseph Cotten.” And my mother says, “Oh yes I do.” He went over and stood at the fireplace while we talked. It was very memorable.

(FR): Did you keep in touch with Olivia de Havilland?

(MK): On our 20th Anniversary, my wife Barbara and I went to Paris to see Olivia. I’d corresponded with her and it was a set date. We were supposed to be there at 6pm for canapés and champagne. I bought her roses and Barbara brought her a bottle of champagne. So we get there and I knock on the door—no answer. Knock on the door—no answer. Finally, this little old gentleman comes to the door who speaks no English. I showed him a letter that Olivia had written to me to set up the date. He opens the door and tells us to come on in. He takes the paper and runs upstairs. Barbara says, “I have a bad feeling.” And I said, “Yeah I do too.” We’re sitting inside Olivia’s house, which in itself was a thrill to me. This little old man became a messenger. Olivia and I corresponded via post-it notes. I have about 20 or 30 of them that we corresponded back and forth on, with this little old guy running up and down the stairs. What happened was that the staff either forgot to tell her or she forgot about it. She doesn’t see anybody unless she’s immaculately groomed. She said, “Now, we could do it tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock.” We had our aeroplane reservations and had to leave to go home. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to see her. We communicated for several years after that and right up until her 102nd birthday. And that was an email! Prior to that, we communicated via snail mail and that was a thrill. I’ve got six of her hand signed letters.

(FR): That’s really special, having those from your movie mom!

(MK): Exactly, exactly.

(FR): Did you ever cross paths with Gable again?

(MK): One of the outstanding things is, he was always a nice man, a gentle man and very good with kids. Years later, I lived in the San Fernando Valley, as he did. He used to ride motorcycles. Coincidentally, a bunch of my buddies and I had a favourite little coffee shop we’d go to on Saturday morning to have coffee or breakfast before we started our day. Clark Gable used to go there with his motorcycle buddies. He’d come in once or twice a month. I’d see him there, but never told him about Gone with the Wind. I just never did.

(FR): This is a bit of a tangent, but the studio commissary has always seemed like the real melting pot of the lot, where everyone working on different films came together. Do you have any stories about your time on the studio lots?

(MK): You’re right! Well, remember I was pretty young at the time and my mother controlled me. When we would go to lunch at the cafeteria, we would go in, sit down, get lunch, eat and leave. I wasn’t allowed to get up and mingle. I wasn’t allowed to speak with anybody. A lot of the big stars at Warner Brothers at the time were there, and it was the same at Republic, Universal, and RKO, but I couldn’t talk to them. I had an interaction with one person at Warner Brothers and I thought my mother was going to die. I had finished school and was sitting out on the porch. There was a movie being filmed at Warner Brothers called Objective, Burma! with Errol Flynn and George Tobias. Errol Flynn was a very gregarious person. He’d walk down the street whistling, saying hi to everybody, things like that. He was walking down the street in his costume and I just wanted to say hello. So I yelled, “Hi Errol! How ya doing?!” I thought my mother was going to have a fit. He called me over and talked to me. When he left, my mother just went up one side of me and down the other.

There’s one more incident that I can recall from about the same time. There was a fella by the name of Gregory Peck who was making his first movie, a war movie called Days of Glory. He was sitting in the doorway of one of the sets, just relaxing, probably going over his lines and thinking of his next scene. I was out for a walk from school. I saw him there and he had a Luger. I walked up and said, “Hello.” I just looked at this Luger, stared at it. He said, “Would you like to see the Luger?” I said, “Yes, I would.” So he took it out, emptied it, checked it, and let me take a look at it. He asked me, “What are you doing here? Are you an actor?” I said, “Yeah, I think so. I’m at school and I’m working on a movie.” The movie was Roughly Speaking in 1944. I just started chatting with him. That was an experience. My mother didn’t see that one because I was by myself. She’d have probably really gone up and down my back on that one too. Now, there was a scene in Roughly Speaking where all the kids are gathered together and are diagnosed with Polio. All the kids are sitting on the floor talking to Rosalind Russell. We were sitting there rehearsing it and this person came out and whispered into Rosalind Russel’s ear. She looked up, blank faced, almost pale, and she said, “My God, we’ve just invaded Normandy.” It was June 6th, 1944. Every time I see the movie I remember the date.

(FR): Red River celebrated its 75th anniversary this year. How did your journey in Howard Hawks’ western classic begin?

(MK): My mother got a call one day and my agent said, “Be at Western Costume at 9 o’clock in the morning to get fitted for wardrobe.” My mother said, “For what movie?” My agent said, “I don’t know the name of it, but somebody will be there to meet you and tell you.” We had no idea. All we knew was that I was going to go and have some clothes put on. We got there at 9 o’clock. 10 o’clock came. 11 o’clock came. Nobody. We’re sitting there waiting. Finally we saw a fella that was the wardrobe master on another movie I did. He said, “What are you doing here Mick?” I said, “I have no idea. We just got a call and were told to be here at 9 o’clock, which we were, and that somebody would be here to meet us. I don’t even know the name of the movie.” He said, “You know something? Those are the same words that I was told. I wonder—I’m doing a western. Was it a western?” I said, “I have no idea.” He called his office and found out the kid’s name is Mickey Kuhn. He came out and said, “You’re it.”

Believe it or not, I worked about ten weeks on that movie with about a week and a half of actual work. We experienced rains in Tucson, Arizona. When they came, I’d be home for two weeks at a time. In the opening scene of Red River, I come in with the cow and Dunson smacks me around a little bit. Now, John Wayne was a perfectionist. He would rehearse a scene four or five times, maybe six. Five easily. Then he would go back behind the camera, look at it, tweak the scene, and he’d come out and we’d shoot it. One time we rehearsed the opening scene while he was behind the camera. He came up to me afterward and says, “Hey Mick, let me tell you something. The scene’s going good, but it would really, really look good if I could hit ya. It’d be just a glancing blow. To connect would really make the scene. Would you mind?” Now I’m 14, he’s 40 and 6′2″. “Yes Mr. Wayne,” I said. Then Howard Hawks called me over and said, “Mick, you know, you’ve got to look kind of tough in this scene, but don’t look tough. You’ll be a heck of a lot meaner and a heck of a lot scarier if you smile when you say these lines.” Which I did, but it was those little tweaks in the scene that made it turn out very well for everybody.

After we shot the scene, they sent the film to Hollywood for development. When it came back two days later, we called that ‘the rushes’, and we’d see scenes that we shot for two days. When that scene with John Wayne was run, where he hit me, after it was over with, he came up to me and he said, “Mick, thanks a lot, that was a great job.” He put his hand out and I shook his hand. I tell everybody I haven’t washed my right hand since 1946. One of the big thrills of my life.

(FR): You’ve worked with a number of former Film Review legends, we mentioned Clark Gable and John Wayne, another is James Stewart, who you worked with in Magic Town and Broken Arrow.

(MK): On Broken Arrow, it was one of those films where there was no interview. I just got called and told, “Be at Santa Monica Airport at 5 o’clock in the morning on this date. You’re going to go to Phoenix, Arizona for a movie.” My mother was afraid of flying, but she had to do it, because that’s how we went. We got to Phoenix and were driven out to the location site. After I got wardrobe and make-up, they said, “Ok Mick, the horses are out there. Get on the horse. It knows where to go. It’s about half a mile to three quarters of a mile over there. You’ll see them shooting. Just go over there and wait. Let them know you’re there and they’ll come get you.” I said, “Ok.” I was 17 at the time, so I was kind of responsible. I rode over and waited about 100-yards away so I didn’t distract anybody. As I’m sitting there, this person starts riding up to me on a horse. He comes up to me and says, “Mick?” I said, “Yes sir.” He said, “It was Magic Town, 1948 wasn’t it? Jim Stewart.” He remembered me. Jimmy Stewart was absolutely wonderful.

(FR): He seemed like a cordial, down-to-earth guy.

(MK): He was a consummate professional actor. When he was in character, he was in character. When he was out of character, he was out of character. Just a nice, nice guy. When I worked for American Airlines, I’d see Jimmy Stewart at the airport. I’d talk to him, but I never told him about Magic Town or Broken Arrow.

(FR): During your career, were there any big films that you ended up on the cutting room floor of?

(MK): In a sense, yeah. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. I had the opportunity of working with Elia Kazan for the first time on that movie. Meet Me in St. Louis. Gosh, there was another one. I can’t remember what it was, but there were three out of 35 that I wound up on the cutting room floor of.

(FR): What was being on Vincente Minnelli’s Meet Me in St. Louis set like?

(MK): When I was working, I just did what I was told. My mother always told me, “Do what the director tells you.” They were all very good to me. Vincente Minnelli, as I recall, was a bit standoffish with the kids.

(FR): He was the kind of director that was probably more internal and focused on getting his shots.

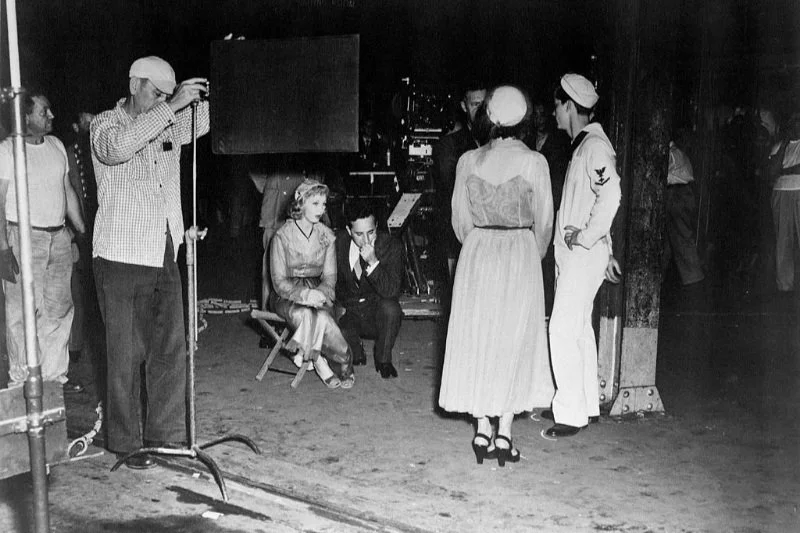

(MK): Exactly, exactly. I did multiple films with Elia Kazan, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn and A Streetcar Named Desire. He was pretty consistent. The interesting thing about him was, he directed his movies, in my opinion, like he did theatre. It’s completely different. You want more out of theatre than you do out of movies, but he directed them just the way he would in the theatre. Like Streetcar, it’s the same as he did it on the stage. Turns out to be a great movie. I was fortunate enough to be in it. I played the sailor that put her on the streetcar in the beginning.

(FR): You were actually a sailor then, weren’t you?

(MK): It was just before I went into bootcamp, yeah. The nice thing about that was it made me (and nobody really cares but me) the only actor in Hollywood to have appeared with Vivien Leigh in both of her Academy Award winners. I’m kind of proud of that.

(FR): You were a good luck charm!

(MK): That’s what I like to think! She won the Academy Award both times.

(FR): You were the one thing in common with both roles.

(MK): Right, I should have told her that!

(FR): What was the set of A Streetcar Named Desire like?

(MK): Meeting Vivien was probably one of the most outstanding experiences of my life. I had just turned 18. This was my first movie without my mother. We got a call that I had to be in New Orleans, Louisiana on location for a movie. No name. No nothing. I flew down to New Orleans. We filmed late at night, because that’s when we could use the train station. We rehearsed the opening scene a couple of times. While we were waiting, I said to one of the crew members, “It’s a thrill for me to be working in this movie with Miss Leigh. 11 years ago I played Beau Wilkes in Gone with the Wind and here I am with her again.” I never did things like that, but it was thrilling to be with Vivien Leigh. The crew member said, “Oh, that’s nice Mick.” We continued on, just waiting around and finally the assistant director says, “Ok everybody, take 30. Mickey, come here I want to see you.” I thought, “What in the world did I do? That’s the end of my career, whatever I did.” Most of the filming was done with pan work, there were no stable cameras, it was either on wheels or walk-around. I went over where the camera was located and I said, “Yes sir?” He said, “Lady Olivier wants to see you in her dressing room.” I thought, “Are they going to send me home? Am I going to have to take the train or will I fly?” He said, “I’ll take you over. When you’re finished, let me know.” I thought, ‘How can I be in control of that?’ I was only 18, I had never been out on my own.

We got over there and I knocked on the door. Her assistant came to the door and I said, “Hi, my name is Mickey Kuhn. Lady Olivier wanted to see me?” Vivien was sitting there and she says, “Oh yes Mickey, come on in.” So I walked in and she said to her assistant, “Would you excuse Mickey and me for a few minutes? We have a lot to talk about and we want to be alone.” I thought “Oh Lord, have mercy.” Boy, she was the greatest. I get chills when I talk about her. We talked about anything and everything. Mostly what my plans were and how my life was going. She was just a great lady. I was with her for about a half hour. She smoked maybe one or two cigarettes at the time, but that was about it. I thought, ‘Here I am with Vivien Leigh’. And she was thrilled! “My gosh, you were Beau?” I said, “Yes, ma’am.” She said, “I can’t believe it. Look at you!” And I thought, “What’s the matter with me?” It was a thrill, we talked for a half hour and then I just had to back out. I was getting so nervous, I didn’t know what to do. I probably had to go to the bathroom. When people say, “What was the greatest thrill?” That was one of them, if I had to classify it.

(FR): Now had you finished shooting the scene by then?

(MK): No, no, we went back and continued working for another two or three hours.

(FR): That’s one of the most remarkable moments in cinema history. That you were the one to show her to the streetcar.

(MK): I have a picture of us. Elia Kazan’s sitting on the edge of the set, on the ground. He, Viven, Vivien’s stand-in, and me. He’s explaining the scene to us. Of course, I read into that scene. When she comes up and starts talking to me, does it appear to you, as it does to me, that she’s kind of flirting with the sailor? I like to think that she was, that Blanche was flirting with the sailor. That’s what my dream is.

(FR): That definitely reads. The fact that you were still shooting the scene after your dressing room conversation supports that too. There was a personal connection.

(MK): My other fantasy is that when Howard Hawks was talking about Red River, Victor Fleming said, “Well I worked with a kid when he was six. He was a pretty good actor and if he’s developed into anything in these years and he’s still there, he’s your guy.” That’s what I like to think, it’s not true. Howard Hawks and Victor Fleming were real good friends.

(FR): A lot of directors, when they have a good experience working with an actor, make note of that. So you never know.

(MK): The guy that directed Broken Arrow, Delmer Daves, he did a lot of movies. My mother knew that he had a picture of me on his desk. He would look at me every now and then to remember what I did. So that was always kind of nice.

(FR): The list of directors you’ve worked with is pretty nice too. Victor Fleming, Elia Kazan, Howard Hawks, Michael Curtiz, Anthony Mann, the list goes on. Did you learn a lot from watching them work or in working with them?

(MK): My God, yeah, all of them. I think about it now, little things that came up or that were said. Like Howard Hawks telling me to smile. Just something small. Even Anthony Mann, he was involved with James Whitmore, Victor Mature and those guys. His direction to me would be more casual, something he would throw out. My ego likes to think that he had confidence in me, in the small part I had in The Last Frontier. That he could just throw me something and I would do it.

(FR): You grew up in the heyday of the great movie palaces. Do you have a favourite memory of going to the movies?

(MK): Oh sure, we would go to the movies just for something to do. The Hollywood Pantages Theatre, Grauman's Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, Warner Bros. Hollywood Theatre. They were all great citadels of the motion picture industry. There’s a little theatre in Detroit, Michigan called the Redford Theatre. A group of people formed an organisation and they did a complete retrofit of the theatre. It reminds me of the ones from when I was a kid. They had events for Gone with the Wind and put my name on a seat at the theatre, so I’ll always remember that. Those old theatres, they were great. My friend Patrick Curtis and I,—a dear friend of mine that had the good fortune of being married to Raquel Welch for about six years—were raised there in Hollywood. We could take a nickel streetcar from where I lived and decide what theatre to go to on a Saturday afternoon, with no worries or concerns.

MICKEY KUHN was a US Navy veteran and retired from airport management with American Airlines in 1995. As a child actor, Mickey is noted for his portrayal of Beau Wilkes in the 1939 classic Gone with the Wind. He is the only actor to have appeared with Miss Vivien Leigh in both of her Academy Award winning performances, Gone with the Wind and A Streetcar Named Desire. In the early 1950s, Kuhn served in naval aviation as an aircraft electrician during the Korean War. The US Navel Institute noted that after Kuhn joined the Navy in 1951, his shipmates were unaware of his acting career until they spotted him onscreen with John Wayne during a movie night. After the service, he appeared in The Last Frontier (1955), Away All Boats (1956) and on three 1957 episodes of CBS’ Alfred Hitchcock Presents, before beginning a 30-year career with American Airlines. In 2005, the Motion Picture & Television Fund awarded him The Golden Boot for his contributions to the Western film genre. Mickey was a nonagenarian and is survived by his lovely wife Barbara, his son Mick (and his wife, Jolene), daughter Patricia and granddaughter Samantha.

Read more about Mickey in our In Memoriam tribute:

Mickey Kuhn (21 September 1932 – 20 November 2022)